Forest monitoring in the South Pacific – Blog #6

One thousand tree tags later (well it was actually 1003, but who’s counting?!) and our forest monitoring on Tetiaroa is complete. So far we’ve used up 100 metres of pink flagging tape, 56 PVC pipes and eight litres of paint to mark the trees… as well as two bottles of mosquito repellent. (A time lapse video of us at work and the celebration of our ‘mille’ (French for thousand) tree are both available on Twitter.)

I’m not divulging how many packets of Tim Tams were consumed in the process, but let’s just say that Walter’s advice about the importance of biscuits for team morale was followed very closely!

Our daily commute across the stunning turquoise waters of the lagoon is guaranteed to be the best commute I will ever have to any workplace – on calm days, the water is like glass, turtles, rays, sharks and speckled moray eels are easy to spot amongst the coral bommies. Elegant black tipped reef sharks and lemon sharks would cruise up and down the beach at sunset on our return (especially when Hinano Murphy and the Tetiaroa Society prepared a traditional “ahima’a” feast for the BBC film crew) and I even glimpsed a whale tail just outside the lagoon (there’s still time to improve on this one)!

But the real work was inside the atoll’s forested motus – walking over the big coral chunks and fallen coconuts, with hermit crabs for company and mosquitos forcing us to dress ridiculously. The Tahitian word ‘fiu’ (pronounced like ‘phew’) is applicable – we’re tired (although the other meanings of fiu relating to boredom definitely don’t apply!), and no one has had the chance to be ‘hupe hupe’ – lazy!

Data crunching and leaf sample processing is almost complete and it’s striking how different the vegetation on each motu is, as well as how much variation occurs within even the small motus. Keep in mind the largest is about 2 km long and no more than 800 wide.

In most forest types surveyed, one tree species has come to dominate, either through human interference (with the coconut plantations) or through other, ongoing ecological processes (see my previous blog post about the different forest types on Tetiaroa). This has meant that completely different types of soils, levels of sunlight and biomass (volume of living material, a proxy for carbon content) are found in each forest type.

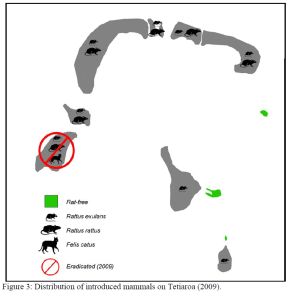

Interestingly, the smallest motu – Ai’e, is the only one where no single species dominates. Instead it is highly diverse, with velvet trees (Heliotropium foertherianum) and miki miki (Pemphis acidula) lining the shorelines and a mix of pu’atea (Pisonia grandis), noni (Morinda citrifolia), coconut (Cocos nucifera) and velvet trees in the interior. It is possibly the least disturbed motu, with no invasive rats, only a couple of planted coconut trees and it is literally covered in nesting birds.

So is the vegetation on motu Ai’e the most natural? Determining what vegetation types are ‘natural’ for Tetiaroa is incredibly difficult, and there is definitely no one optimal forest type for the entire atoll. The important thing is that we now know what our baselines are, given changes are afoot…

Determining what vegetation types are ‘natural’ for Tetiaroa is incredibly difficult

One such change is rat removal. James Russell’s team are planning rat eradication experiments. On most of the motu, introduced Polynesian and black rats eat native tree seedlings and the eggs of nesting birds. However, they also eat the nuts of the invasive coconut trees, limiting the number which germinate and grow to compete with native plant species.

So how will removing rats effect these ecosystems? Will the number of coconut seedlings skyrocket? How quickly will birds return to nest on previously rat-infested motu? What subsequent changes can we expect in nutrient cycling and tree growth with an increase in bird poo raining down on our tagged trees? Will our plots on Rimatu or Reiono, the motu where trial rat eradication efforts are likely to start, respond in the same way as the plots on the other motu, given differences in the ecological communities present?

There are many questions to explore in this gorgeous natural laboratory, and our baseline forest inventories will provide valuable references in the years ahead.

James’ efforts aren’t the only eradication program going on in Tetiaroa – an innovative method involving the bacterium Wolbachia is used to control the mosquito population on Onetahi, where the hotel is located and staff live (there is an interesting explanatory article in Nature). Hervé Bossin, Manea Brando and their team at Institut Louis Malardé (ILM) on Tahiti, are making plans to expand this mosquito control program across the entire atoll. The information we have collected on vegetation type and density (and our own personal experiences!) will assist them in determining hotspot areas and priority sites for the eradication efforts.

For now, we’re back at UCB’s Gump Station, setting up two more plots on Moorea, in steep valleys like this one with giant mape trees (Inocarpus fagifer, Tahitian chestnut). Heipoe and I are hoping to work with several organisations here and are looking forward to being joined by students from the Université de la Polynésie français for their field trip in a few weeks’ time.

UPDATE: Days off are definitely an important part of any field trip – a mother humpback, calf and male suitor were seen jumping and playing during the surface interval on today’s dive!

You must be logged in to post a comment.