The New Forest, where a national park is home to grazing animals, and the name ‘New’ is almost 1000 years old.

In many parts of the world, scientists and land managers struggle to entice others to engage with challenging biodiversity conservation issues. Not so in the New Forest in Southern England, where around 160 people turned up for the New Forest Knowledge Conference yesterday.

Despite the name, the New Forest was originally designated as a royal hunting forest by William the Conqueror in 1079 (it was originally known as Nova Foresta) and has been continuously managed for its natural resources, particularly deer and timber, ever since then. It is recognised as one of the best sites for lichens in Europe, is home to almost all of the UK’s reptiles and is known for its stunning ‘Ancient and Ornamental’ deciduous woodlands (check out the excellent book Biodiversity in the New Forest edited by Prof Adrian Newton).

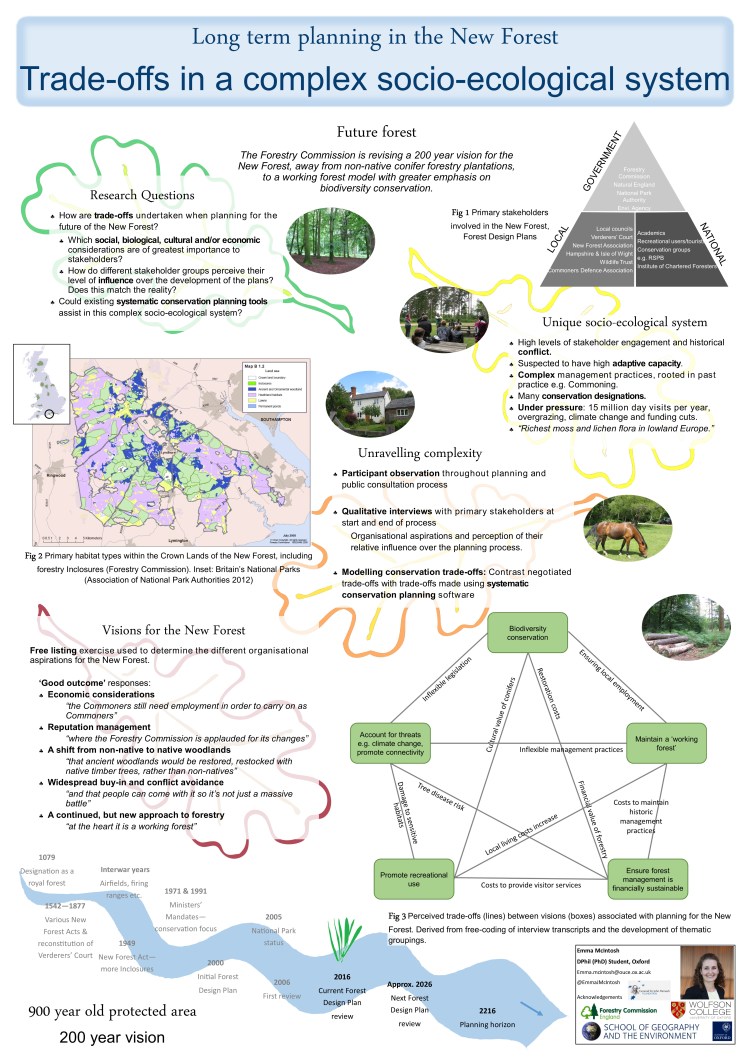

Today the New Forest has more layers of protection and recognition than almost any other site in the U.K., including over 20 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), Ramsar Convention sites, and since 2005, National Park status. In addition, the area must be managed to accommodate tens of millions of visitors a year, the towns and villages within the boundaries of the National Park, and the ‘working forest’ culture and history of the Commoning community. As an Aussie, this type of ‘cultural landscape’ wasn’t what I used to think of as a national park, but its complexity is fascinating.

As you would expect, there is a great deal of interest in the unique ecological communities of the New Forest and in how they are managed, making the subject of today’s conference so welcome. We heard about the consequences of recent beech dieback in the forest from Paul Evans, and Elena Cantarello explained how multiple pressures such as overgrazing and climate change can dramatically reduce the resilience of many natural, financial and recreational values of the forest.

The day was also full of surprises, I learnt from Becky Spake that ectomychorrizal fungi (which partner up with tree roots in the soil) are as diverse in the soils of 180 year old managed woodlands as in 1000 year old ancient woodlands (read Becky’s 2016 article in Biological Conservation), and that despite being an introduced species, Douglas Fir is a favoured habitat by many sought after birds such as the Hawfinch and Goshawk (check out the Wild New Forest website for more updates like this).

All the wonderful geeky ecology stuff aside, the most valuable part of today was the willingness of so many to engage, and the New Forest Knowledge Projects’ efforts to bring us together. Presenters represented five universities and research organisations, and delegates included staff from local Parish councils, the National Park Authority, Forestry Commission, environmental non-profit organisations, university students and interested members of the local community.

There aren’t too many circumstances where retirees and students-alike are happy to sit through hours of figures and tables of data, nor are there many other places where land managers welcome advice from strange people who spent their summers poking around on their land. Such is the draw of the New Forest, and this collaborative attitude is vital as big changes are afoot.

Climate change, human population pressures and tree disease risks are very much on the agenda, and even commercial forestry operations will need to adapt – many common forestry species will be unsuitable in the New Forest within 50 to 100 years (according to Gail Atkinson from Forest Research). Good timing then to discuss the 200 year vision currently being finalised by the Forestry Commission.

In my presentation I was able to draw together the many issues raised throughout the day in light of the current Forest Design Plan process and the long term vision for the future of the New Forest. The Forestry Commission manage the Crown Lands that make up most of the National Park, including a large number of forestry ‘inclosures’ (which are mostly fenced, managed areas). Following extensive consultation, they have committed to increase the cover of native woodlands inside the inclosures from around 20% to 45%, whilst reducing coniferous plantations from around 33% to 3%.

This is all great news for the forest and raises lots of interesting questions about how best to maintain a ‘working forest’ alongside biodiversity and recreation considerations. I have ideas about how systematic conservation planning tools could aid some of these multidimensional questions, but more on that another time!

In our closing discussions the need for constructive dialogue and collaboration amongst all involved in the New Forest was emphasised by Chris Short and others. Despite the fact major disagreements continue in parts of the forest over stream restoration works, the workshop discussions were respectful and positive, so I hope to see many more New Forest forums like this in future.

And a little extra…

A few hypothetical questions I didn’t get to throw in the ring this time but would love to debate next time:

- What would happen if we took all the fences down around the forestry inclosures and allowed greater physical connectivity between habitats and the deer and grazing animals which browse on them?

- How suitable are current environmental and biodiversity legislative requirements for the New Forest’s protected species and habitats in a changing world? Are rigid laws preventing adaptive management from being trialled?

- Is it possible to quantify biodiversity conservation objectives to start determining which are currently being met and which need much more work to achieve?

- How can the general public be bought along with, and encouraged to anticipate future changes (be they management changes or natural changes). Alterations to forest cover or species abundance often result in knee jerk, negative responses from the public which can raise unnecessary conflict.

And if you’ve hung around to read right to the end, here is a poster I prepared a while ago on some interviews and observational work I have been undertaking alongside the Forest Design Plan consultations.

You must be logged in to post a comment.