By Emma McIntosh (University of Oxford) & Glenn Althor (University of Queensland)

Banner image: Early morning in beautiful Stockholm. Credit: @NealHaddaway

This week we were privileged to attend the First International Conference of the Collaboration for Environmental Evidence (CEE) in beautiful Stockholm! Attending were a diverse collection of 100 other students, researchers, consultants, policy makers and NGO staff, from a variety of nations.

The conference byline was ‘Better Evidence, Better Decisions, Better Environment’. Although, Prof. Andrew Pullin (co-founder of CEE) gave an honest acknowledgement that the process of linking evidence to impact is neither linear, nor guaranteed!

Attendees were bought together by CEE, due to our shared interest in evidence synthesis; the systematic and rigorous collation of available information on a particular topic, with the aim of determining the best approaches to meeting important policy needs, in particular addressing environmental management challenges.

It’s been an incredible learning experience, which we wanted to share! We’ve put a list together on some of the important and useful things we have learnt. We hope they will be of value to anyone interested in conducting better evidence syntheses.

- Evidence based conservation is important! When you have limited resources to spend on conservation or environmental management measures, it’s essential to spend it on the interventions which evidence suggests are the most effective.

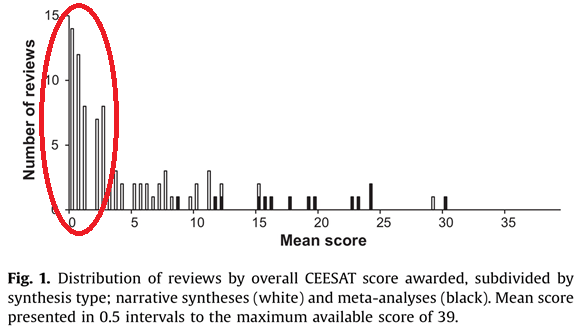

- The majority of existing literature reviews which call themselves ‘systematic reviews’ aren’t meeting the basic acceptable levels of rigour. High quality reviews aim for objectivity, transparency and comprehensiveness. Tell people what you did for starters! Ignoring these basic principles can lead to reviews being misleading at worst, or unusable at best. (Figure link O’Leary et. al. 2016)

- “Where traditional reviews are used, lessons can be taken from systematic reviews and applied to traditional reviews in order to increase their reliability.” – Haddaway et al. 2015 Conservation Biology, 29(6), 1596–1605.

A selection of Haddaway et al.’s suggestions (taken from Table 1 in the above paper):

- Plan questions, desired outputs, and inclusion criteria before starting, and consult with subject experts.

- Include all viewpoints by searching multiple databases.

- Include searches for unpublished (grey) literature to account for publication bias.

- Screen all search results with the same predetermined criteria.

- Create basic critical appraisal tools to categorize articles as of low, high, or unclear quality.

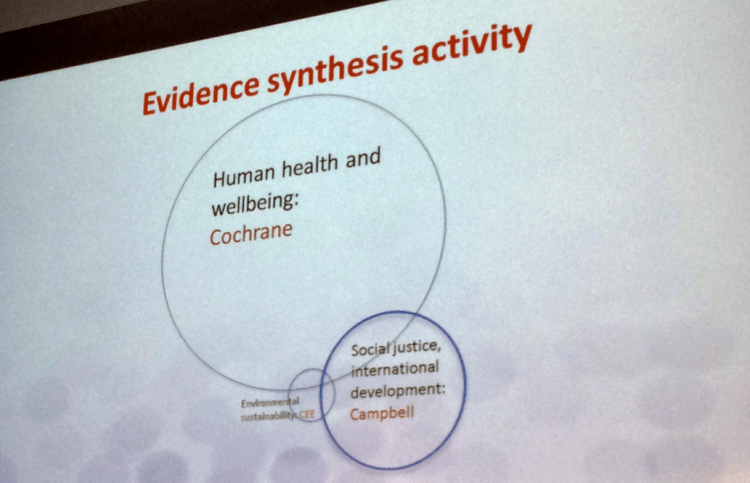

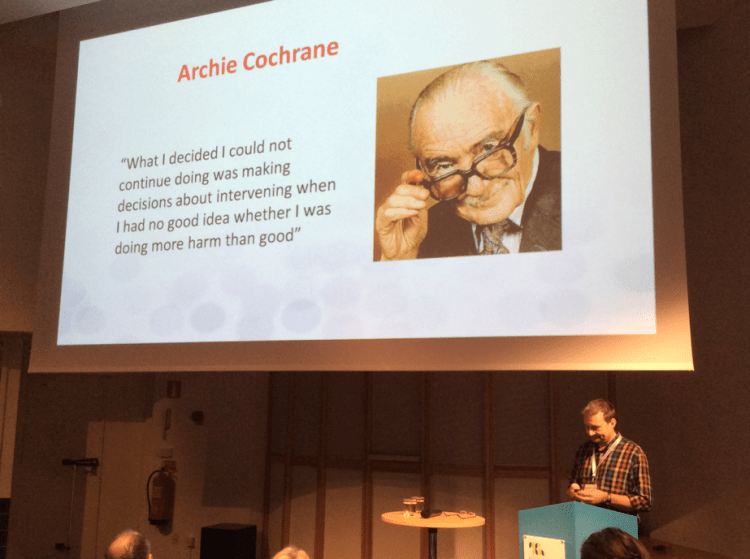

- Evidence synthesis is still in its early days in the environmental literature, but it is very well established in healthcare (Cochrane) and the social/development sector (The Campbell Collaboration), so much of the CEE methods have built upon these tried and tested approaches.

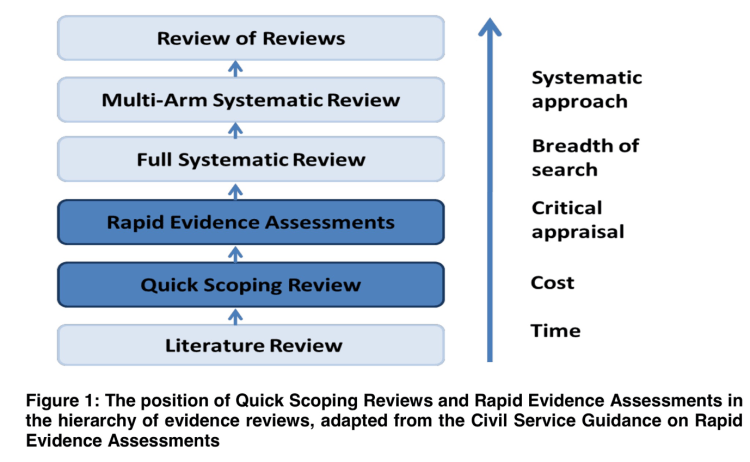

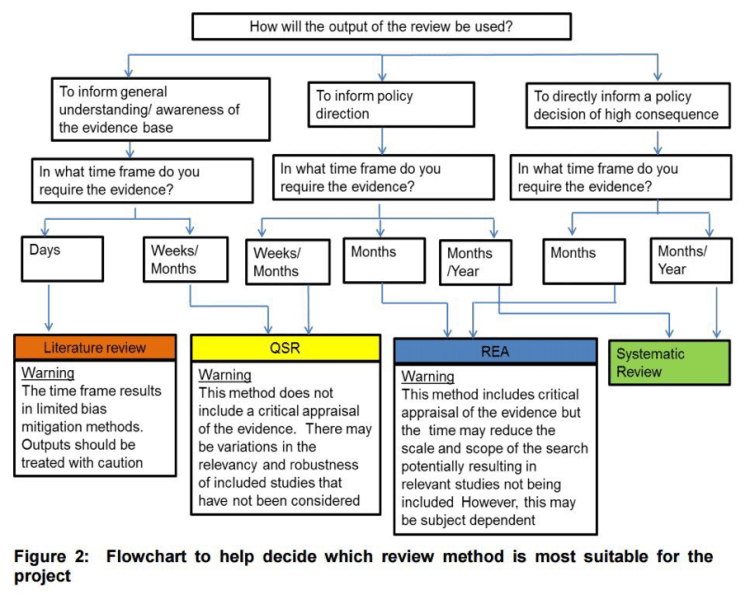

- Systematic Reviews might be the gold standard type of literature review, but there are other valuable options. These can also include Rapid Evidence Assessments and Quick Scoping Reviews. These methods offer a much faster way to undertake evidence synthesis, but are also much more risk sensitive. (Figures from Collins et. al. 2015)

- Shortcuts increase risk! Understanding the risk of impact that your synthesis can have is critical! E.g. Will your review influence human well-being policy? If so, reviewers must ensure their synthesis is as rigorous as possible.

- The quality of primary research is very important too. Primary researchers need to better understand what evidence synthesis is. If primary research is to be used in syntheses methods, such as meta-analyses, authors and editors need to ensure that papers aren’t ‘just good enough to get published’. They must also consider if their methodology is sufficiently detailed and rigorous.

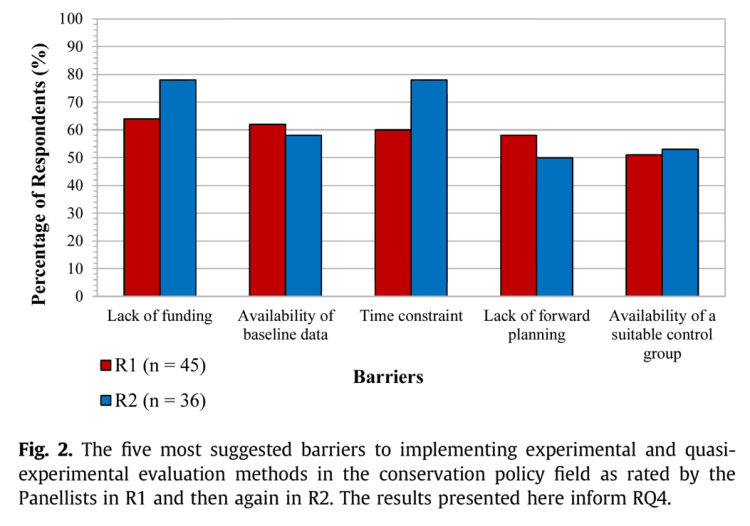

- There are many barriers to policy makers and practitioners when conducting evaluations in the first place and these are often under-acknowledged. Practitioners are trying, but it’s not always feasible to implement the kinds of experimental controls which might be most desirable. Groups like CECAN (Centre for the Evaluation of Complexity Across the Nexus) are working to develop feasible but robust measurement options, and people like Nick R Hart at the US EPA are demonstrating how barriers can also be facilitators for evaluation. (Figure from Curzon & Kontoleon 2016)

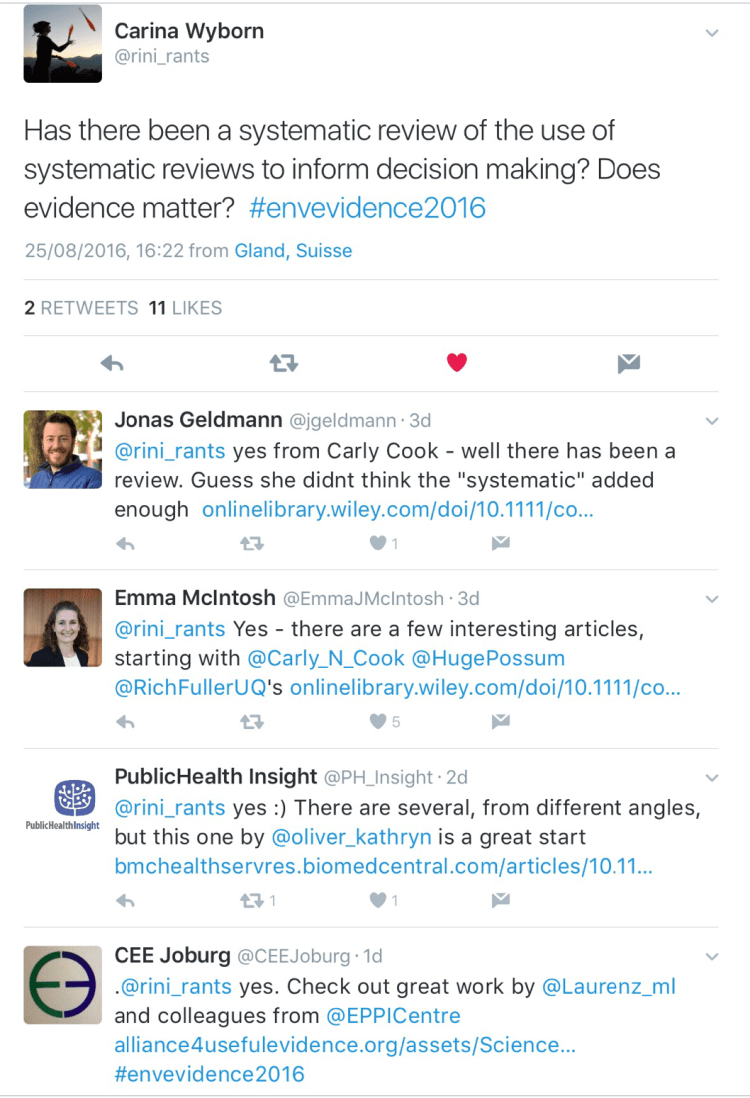

- There have been reviews of the use of systematic reviews! We do actually know when and how to ensure carefully synthesised evidence is accessible, relevant and timely (it just takes a bit of work!)

- Systematic Reviews are hard! Selling evidence is hard! Evidence synthesis can be resource intensive, which can also make it difficult to find buy-in from policy makers. Addressing this gap is important if scientists want to ensure that policy is best evidence based! (Check out Evidentiary’s website)

We want to thank the British Ecological Society and Mistra EviEM for providing support for us to attend this conference.

If you found this useful and want to know more, please contact either of us (@GlennAlthor or @EmmaJMcIntosh), or check out CEE’s website. Happy synthesising!

You must be logged in to post a comment.